Shipwreck in Lučice

At the location near the bay of Lučice, on the southwest coast of the island of Brač, lie the remains of the iron wreck of a sunken steamship. Due to the size of the site and the abundance of small inventory from the ship, the site represents an important source for the study of the equipment of steam ships from the 19th century, and the steamer itself possesses characteristics essential for the valorisation and study of the typologically-structural elements of steam ships in general.

Witches in Witch’s Port

The bottom of a beautiful bay on the western side of the island of Brač, which branches into several smaller bays, is the perfect place for sheltering ships from all kinds of bad weather. The largest of these bays is Vičja luka (Vještičja luka, Witch’s Port), which gave rise to many superstitions and legends. It is believed to be the place where witches dance and gather at night, and also that it is connected by secret underground canals to the notorious Vičja jama (Vještičja jama, Witch’s Pit) on Vidova gora. The most famous legend is the one involving a pair of oxen who fell into Vičja jama, after which their yoke emerged in Vičja luka after some time.

Vitalac

Since ancient times, it has been believed that Bobovišće was the first place where legumes and broad beans arrived, and also that the vitalac, an Ancient Greek dish, arrived at Brač via Witch’s Port, where four prehistoric graves covered with stone slabs were discovered, featuring multiple burials and a rich collection of grave goods from the Illyrian Greek civilisation.

Legends

Fishermen used to believe in the existence of macići – dwarves with red caps – which is why, after arriving at their fishing position, they would call out: Mace, Mace, where are we going to put the net? Or Mace, Macić, the first fish I catch will be yours, just help us! After catching the first fish, they would throw it ashore and shout: Here you go, mace, lunch. They believed that the first fish should be thrown to a macić, and then they would have better luck at catching more, as the macić would chase fish toward the net. “There exists a story that tells the tale of how one fisherman became a rich man thanks to a macić. The name of this story is Macić, blago iz mora (Macić, Treasure from the Sea).

Customs

When a ship was built, priests would be called to bless it, after which ceremonies were held. The ship would be decorated and a flag would be put on it, after which one wreath would be placed on the bow, and one on the stern. A bottle of prosecco would be ceremoniously broken on the bow, after which the ship was considered to have been baptised. Then they would lower the ship into the sea, after which a party was thrown in the shipyard. The timbre for the construction of the ship would be cut from Mary to Mary, that is, between the Feast of Our Lady of Mount Carmel and the Assumption of Mary. The fishermen were very superstitious, so if they met a crooked (limp) woman when going fishing, they would return home and not go fishing as, according to their beliefs, such an encounter brought bad luck. They also thought it was bad luck to see a widow, a priest, or a rabbit, and some fishermen would return home at the mere mention of them.

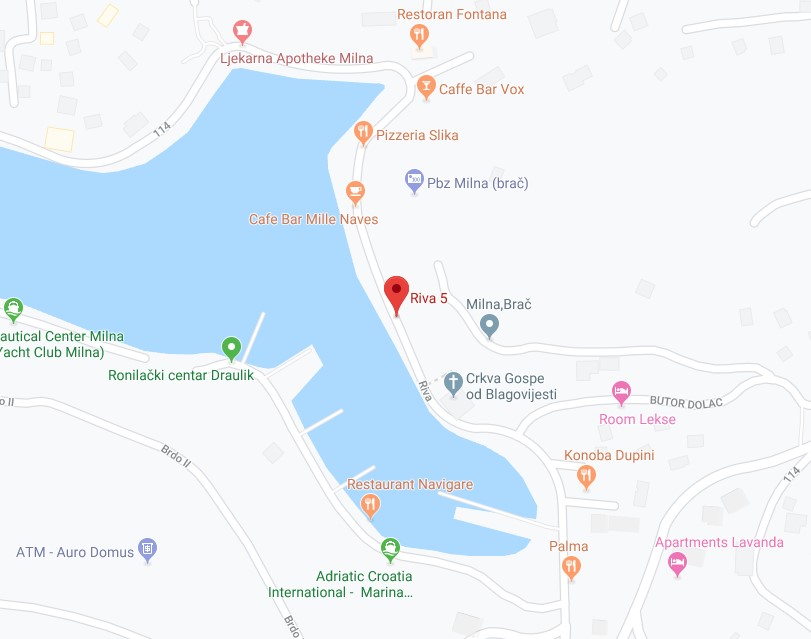

How the people of Milna came to their senses in Venice?

The inhabitants of the island of Brač love to joke around, and even make fun. Here is how the locals of other villages like to joke with the people of Milna.

Between Brač and Šolta there is a small island, Mrduja. There exist many stories related to this island. One such story relates that the people of Milna earned a lot of money, and concluded that it would be wise of them to buy a little more sense. They agreed that it would be best to send two or three traders who spoke Italian to Venice, so they could buy some sense. So, they went there by boat and bought some sense from the local merchants. The Venetian merchant gave them a flask that was well sealed and said: Here, your sense is in this flask. When you arrive at Milna, summon all the people of Milna to the town square and open this cork. When you open the flask, sense will slowly start pouring out of it and entering their heads, making everyone smarter. Delighted, the traders from Milna embarked their boat and made their way slowly to Brač.

Then, one of the traders started contemplating everything, and said: “If we bring this flask to Milna and let the sense out, everyone will become smart, and what use would we have from that? I think it would be best if we stole a little bit of it, so that we can be smarter than the others. ” The other three agreed and said: “Best we made a stopover at Mrduja before returning to Milna.” So they did. They landed on Mrduja, opened the flask and concentrated hard, hoping that the sense would enter their heads better once the flask was opened. However, a mouse escaped through the opening of the flask, and when they saw this, they started shouting: ” Oh my, our sense has abandoned us, what are we going to do? We will all lose everything, our money and everything we have paid. ” However, after all, they decided to be fair and concluded that the best thing to do was to pull the island of Mrduja into Milna Bay, so that sense could slowly pour from it and make everyone smarter. So, they went to Milna to tell the other villagers what they had done.

The locals took a large rope, put it around the island and started pulling. But it was by no means clear whether the island was approaching Milna, or if the rope was merely stretching. Then one of them shouted, “Either Mrduja is being pulled or the rope is being stretched!“. Since then, the people from other villages on Brač have been using this sentence to mock the people of Milna.

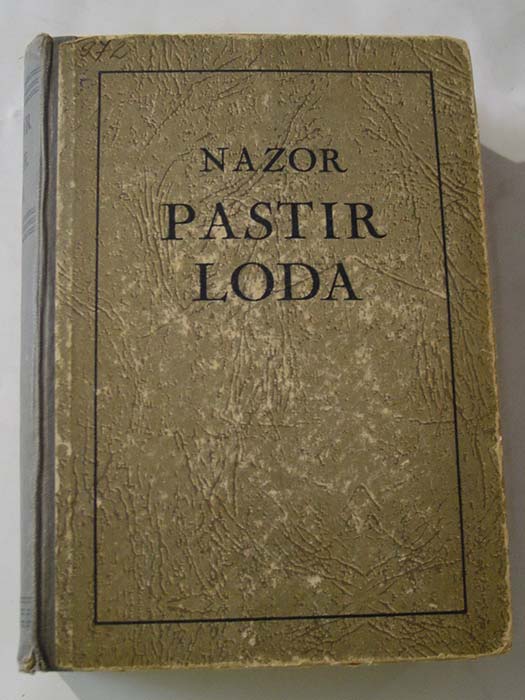

Shepherd Loda

Shepherd Loda, real name Anton Sapunar, born on 20 September 1895 to mother Vica and father Petar, was one of eleven brothers and sisters and lived in Ložišće. He is the topic of the eponymous novel written by famous Croatian writer Vladimir Nazor, but who was he in real life?

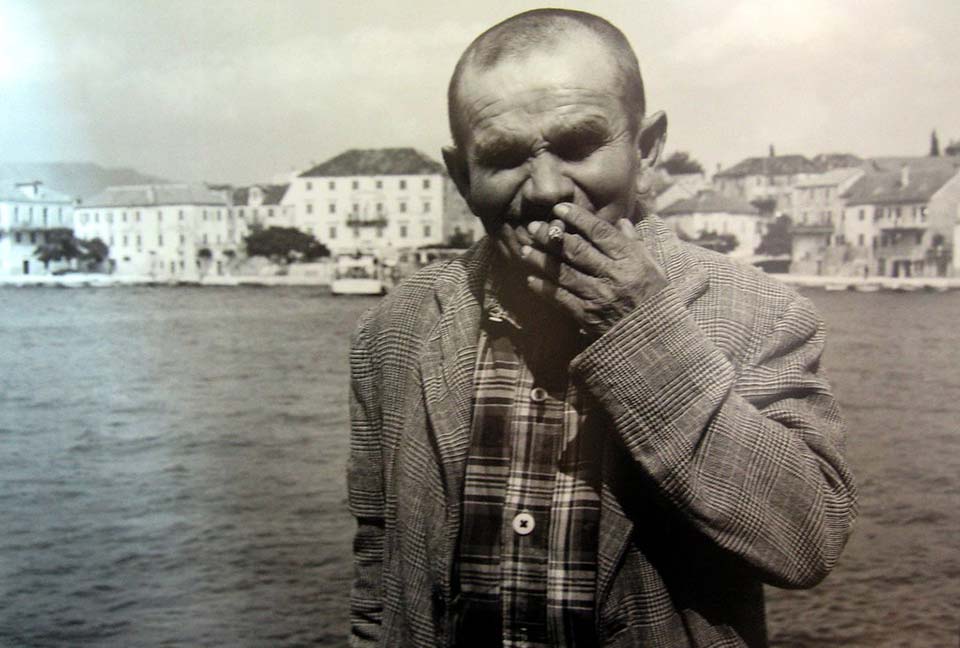

He was low in stature, almost a midget, and mentally on the slow side. He lived in Ložišće with his sister Haramina, near the bell tower. He came to Milna once a year, always for the feast. As he was of cheerful spirit, everyone would gather around him, especially the children. He had the mind of a child of five or six, never went to school and could not read and write, but he knew several rhymes that he had learned from Vladimir Nazor. Whenever the children asked him to sing, he would climb on a small table or column and recite the rhymes. They would give him a coin afterwards and he would be very grateful.

After the war, the feasts were no longer as well organised as they had been before, as they were of religious character, and as such efforts were made to suppress them. Nevertheless, this did not stop Loda from coming. During this period, he would always appear in a trenchcoat, even though it was midsummer. When someone asked him where he got his trenchcoat, he would say with great pride: “Our poet Nazor sent it to me, Vladimir Nazor gave it to me.” And he always had a smile on his face …

He died on 06 April 1975 and was buried at the local cemetery in Ložišće.

Chakavian dialect from Milna

Together with Supetar and Sutivan, Milna is one of the three towns on the island of Brač where the Chakavian dialect has remained preserved since ancient times.

Sutivan’s Chakavian idiom has been preserved only in traces, while the Supetar one has almost disappeared. Therefore, the Chakavian idiom of Milna undoubtedly deserves special attention. This idiom belongs to the South Chakavian dialect and boasts many special features at all linguistic levels, especially at the phonological level. Milna’s idiom speech is characterised by the Ikavian reflex of jat, which is also an important characteristic of the South Chakavian dialect. Just like in the majority of South Chakavian idioms, the ˝ć˝ sound has not remained preserved – instead, we can find the middle c.

Since 2017. Milna’s idiom is a protected intangible cultural good of the Republic of Croatia.

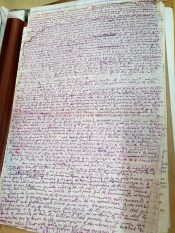

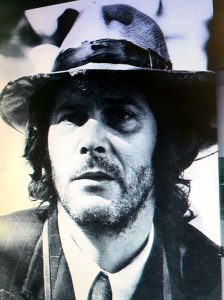

About the character of Cervantes

All who are acquainted with the life and work of the legendary Miljenko Smoje are also familiar with one of his “most heartfelt” characters, that of the local bohemian Cervantes. However, few are probably aware that the character of Cervantes, who was ingeniously embodied by actor Ivica Vidović in the legendary television series Malo Misto, was inspired by a real person – Rade Harašić, a native of our very own Milna, who was born on 11 January 1917. Originally from Milna, he was a returnee from Chile who was convinced that he was a great artist and painter, and he was also a Jack of all trades. He assumed various roles in different parts of the world (from America to Europe, from Brač to London, from Osijek to Milna). Tidy and clean, he would emerge from his stone house on the Milna waterfront (which didn’t have running water) as if it were the most stylish hotel, always looking like a gentleman. He was also a polyglot, and he translated texts into five foreign languages. He was a cat lover who often wrote about his cats, and he eked out a living by drawing portraits of citizens. He had his own boat, and sometimes he would fish and set fish traps. He was also a collector and numismatist.

In the series, Cervantes is also a returnee from Chile whose real name is Antonio Puhalovich – a local bohemian, layabout, vagabond and eccentric. Always dressed in a shabby, tattered suit, trousers too short for him and an old, dirty hat, he spends time sleeping late, contemplating and supposedly translating Cervantes’ “Don Quixote.”

In one episode of a series, a fire broke out in the attic where he lived, and although firefighters rescued him, he returned to the fire-ravaged house to answer the accusations of locals that he had not actually written anything, thus meeting his tragic demise. The scene of the fire in the series was inspired by an actual event, when a fire broke out in the attic of the house where Rade Harašić lived, and he tried to save all his writings, paintings and notes. Though he managed to save one part of them, most was burned in the fire, as was the space in which he lived. In real life, he did not end his life in a fire, and the Milna Town Council allowed him use of the premises of the priest Bonacci in a house on the waterfront of Milna, which is where he spent the rest of his life. One of his last adventures was when he paid for a taxi to take him from Milna to London. Though his life and remembrance of him still evokes all kinds of images, both sympathetic and antipathetic ones, the fact remains that he was a truly interesting individual. He died on 15 November 1991 and was buried at the local Milna cemetery.